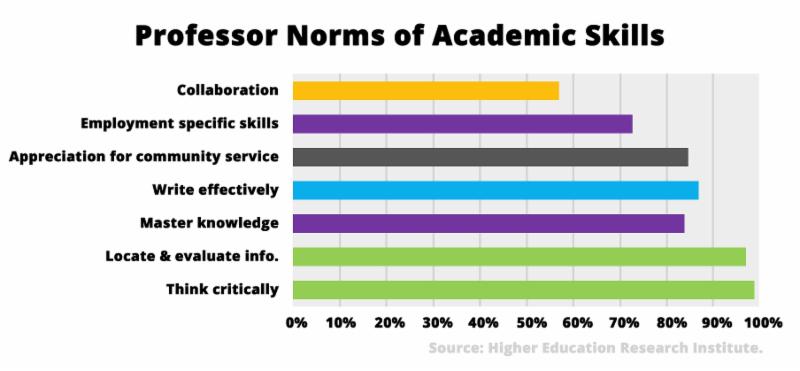

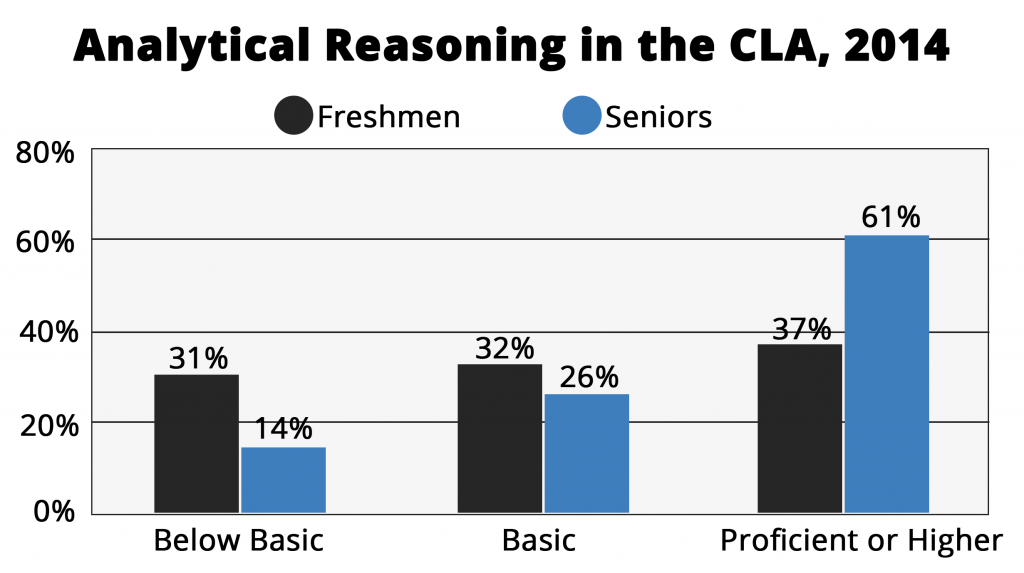

One of the few standardized tests that assesses the analytical reasoning skills of college students is the Collegiate Learning Assessment. The Mastery Level of the CLA+ requires students to solve an analytical reasoning problem and write about it. Some scholars believe that the performance tasks in this test are too general and too easy. However, even if the score is slightly inflated, this news is still not good.

Two-thirds of college freshmen are not proficient in analytical reasoning. Equally concerning is the fact that four years later, after the less proficient students have dropped out of the system, the more select group of seniors is only 61 percent proficient in analytical reasoning. This evidence seems to back up the complaint of employers that the graduates that they hire do not possess quality problem solving skills.

The students who drop out of the system, as well as those who stay in it, are in need of more robust training in analytical reasoning. Without it, they cannot become proficient from the passive position of listening to a professor. Therefore, active learning methodologies are necessary for professors who want to train students in this valuable transferable skill. The keys to active learning are:

- Students are actively using application and analysis learning behaviors.

- Students clearly understand the breakdown of the analytical process and can evaluate their choices alongside other possibilities.

Active Learning → Analytical Reasoning

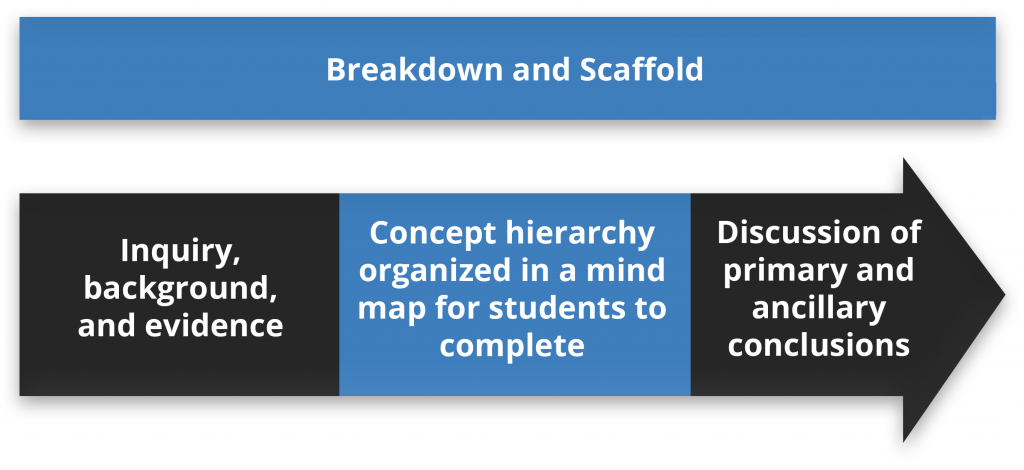

How do you train college freshmen to use an analytical process, as well as reflect upon it and improve it? Again, you need to break down the process into the following components:

- Inquiry, background, and selected evidence

- A scaffold of the key thinking process of applying and analyzing with a mind map or organization of the concepts that will answer the question

- A professor-led discussion of the conclusions, as well as a review of the analytical processes that led to the conclusions.

The above breakdown can be used for more complex problems that use sources. Less complex active learning activities might include the following:

- Giving data or information to students and having them respond to some provocative question using a poll quiz in class or by writing brief response papers

- Providing a document or evidence and a series of questions that require students to break down and understand the document better

- Simply giving a five-point quiz or poll in the midst of a lecture that asks students to apply a concept to a given case

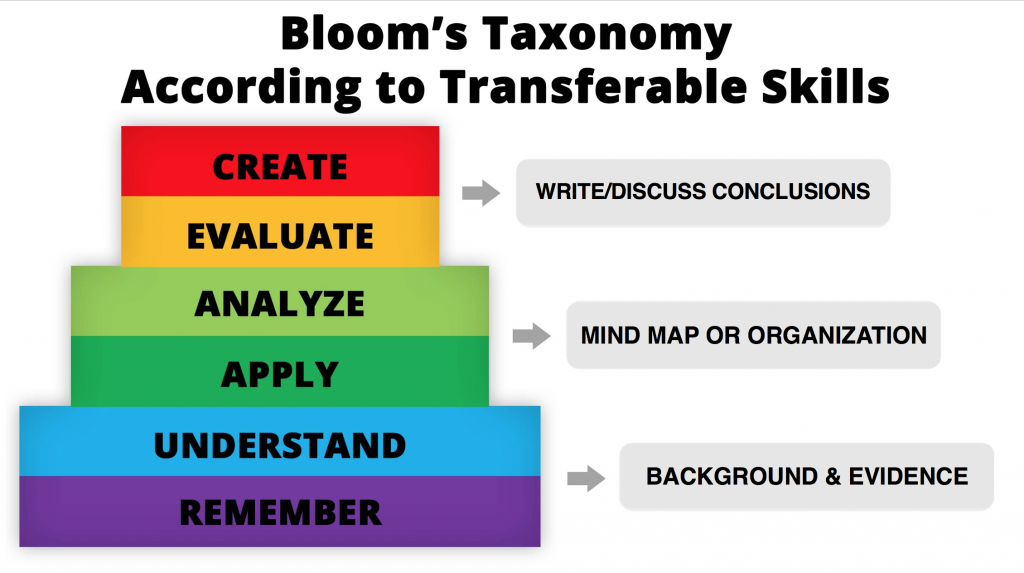

A look at Bloom’s Taxonomy shows once again that analytical reasoning uses all the learning behaviors that appear in the charts I’ve presented.

Professors do not have to turn their courses upside-down in order to make these changes. In fact, I encourage professors who are transitioning from traditional, lecture-only teaching styles to go slow, steady, and small. The more exposure that students have to these small active learning opportunities, the better. You should learn how to manage students, develop your own discussion style, and experience what works best for you and your students before trying more ambitious activities.

Active Learning Lecture → Lecture + Active Learning Activities + Polls

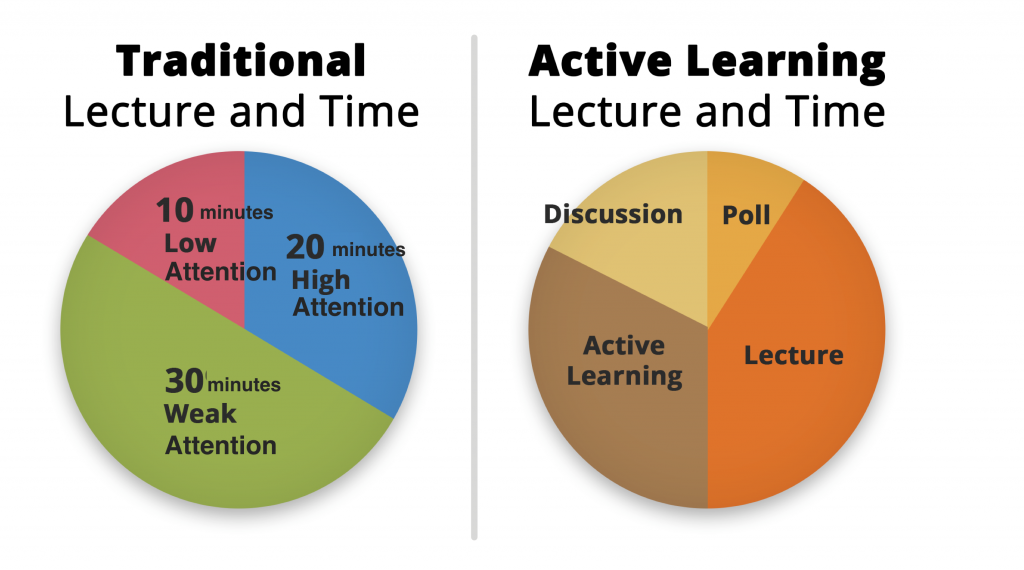

I recommend blending a lecture-based approach with active learning strategies. The lecture platform is essential to the classroom, but one of its major problems is that it works against the human attention span. The research below demonstrates this phenomenon:

- Forty percent of the time, students are not attentive to what is being said in a lecture.

- After the first 20 minutes, student attention drops off dramatically.

- Students retain 70 percent of information in the first 10 minutes of lecture, while they only retain 20 percent of the information from the final 10 minutes of the session.

Below is a physical representation of how the attention span works in a traditional lecture setting versus an active learning lecture structure. In the traditional lecture, there are 20 minutes of high attention followed by 30 minutes of weak attention, and, finally, 10 minutes of low attention.

An active learning lecture setting on the right incorporates several activities and learning behaviors from understanding, to analyzing, to evaluating. These activities periodically revive the brain’s ability to attend and participate. The first 5 minutes involve a poll or quiz to introduce and pique interest in the lecture. This segment is followed by 25 minutes of traditional lecture, which occurs within the timespan that students still maintain high attention levels. In the third segment, however, students switch gears. They form groups among themselves and discuss the independent work they have completed on an active learning problem that is related to the lecture and they process to discuss their findings with one another for around 15-20 minutes. In the final 10 minutes, the professor discusses the conclusions of the activity with the whole class. If there is an additional 15 minutes of class time, the professor may return to lecture, confident that the students are beginning a new attention cycle and will retain what is now being presented.

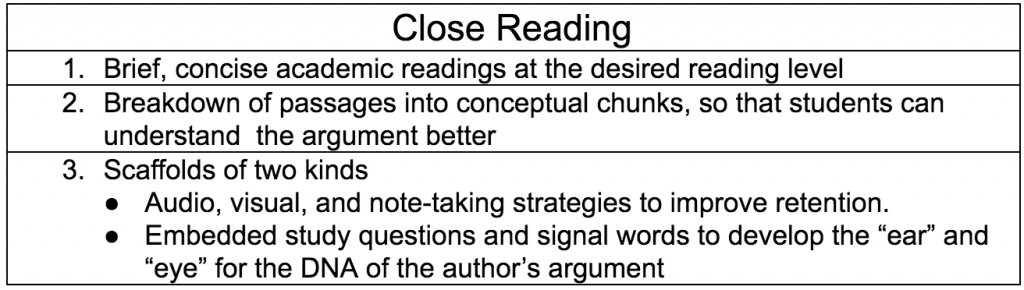

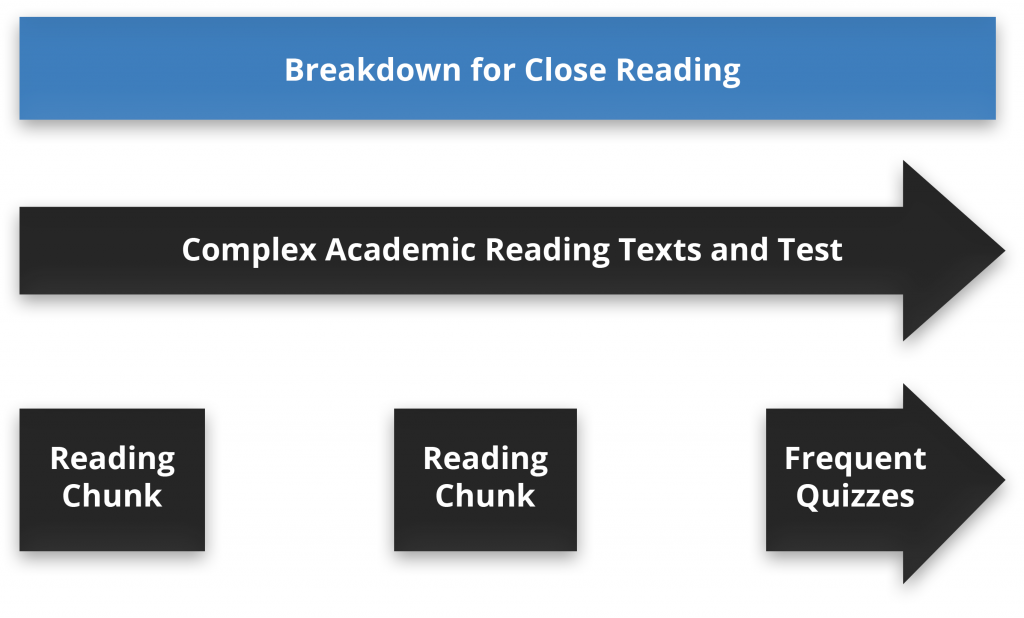

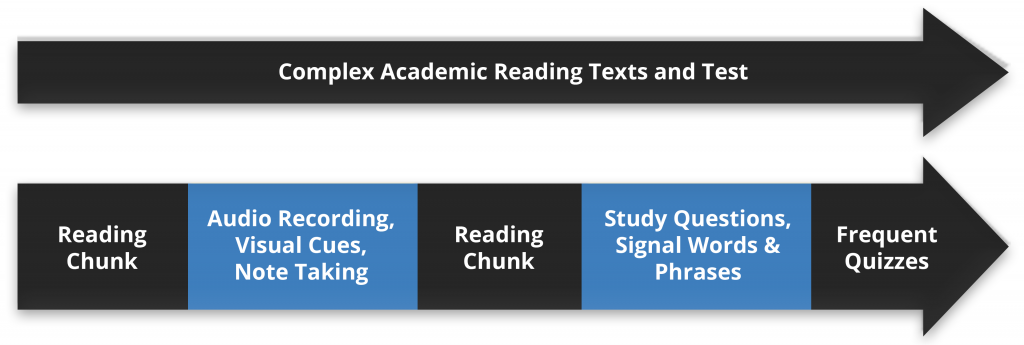

Finally, you want to be sure that the frequent quizzes you are assigning contain questions that are detailed, conceptual, and inferential and which can be linked directly to the study questions and signal words and phrases. You may allow the quiz questions to be on the easier side in the beginning–however, you should make sure that you are not assessing answers on a study guide, but drawing from the actual assigned reading. This ensures that the students’ reading comprehension levels can be evaluated and improved.

Finally, you want to be sure that the frequent quizzes you are assigning contain questions that are detailed, conceptual, and inferential and which can be linked directly to the study questions and signal words and phrases. You may allow the quiz questions to be on the easier side in the beginning–however, you should make sure that you are not assessing answers on a study guide, but drawing from the actual assigned reading. This ensures that the students’ reading comprehension levels can be evaluated and improved.