Writing is the most difficult, and yet the most valuable transferable skill. Unfortunately, few students arrive at college with the ability to write proficiently, and not many become proficient writers while attending college.

Various studies indicate that the percentage of entry-level freshmen who write proficiently at the college level ranges from the high 20s to the low 30s. A recently published and notably provocative book about the lack of learning that takes place in college, Academically Adrift, bemoans the fact that college students are not asked to write enough. Students who were surveyed reported that they were only asked to write a total of 20+ pages in about 50 percent of their college classes.

Based on my own experience, I suspect that these numbers are inflated. First, proficiency tests are based on writing prompts and samples that are at a much simpler level than those required by the social science minimal writing standard (which is about 8 pages worth of thesis-driven argument that integrates a variety of evidence sources and material). Moreover, a minority of students in my own surveys of undergraduates at a four-year university indicated that they had written more than 5 pages in lower-division college courses, let alone 20.

I believe that about 15-20 percent of college freshmen are proficient in social science writing. As a result, my goal was to train another 40 percent of students in a lower-division history course how to successfully craft and compose a standard social science paper. In my experience, prioritizing history writing in lower-division courses was both gratifying and beneficial. Student evaluations read: “This is the first time in my life that a teacher has really showed me how to write.” It turns out that students do not balk in the face of a challenging writing assignment if they have a clear, detailed road map that lays out exactly what is expected of them.

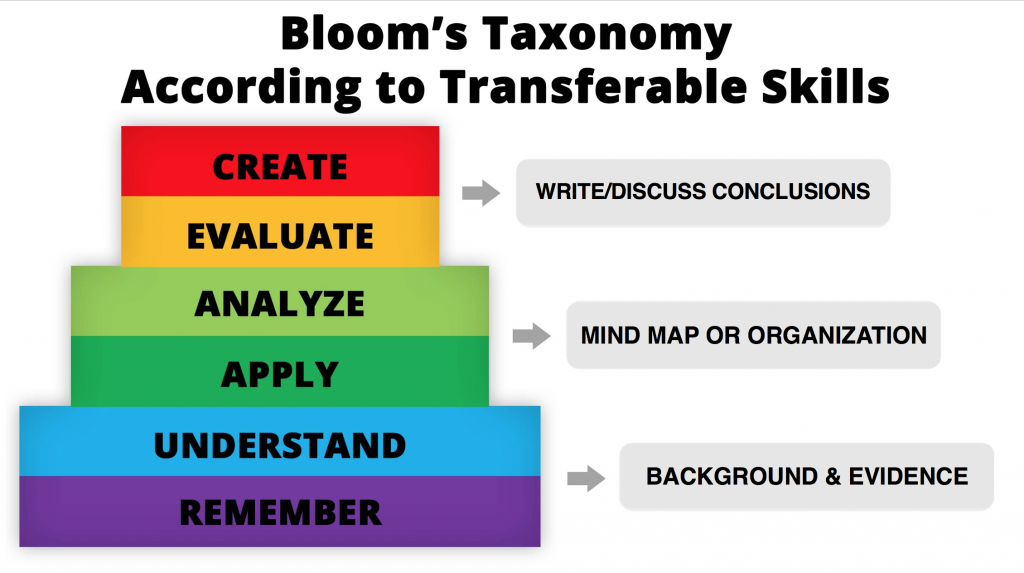

A solid writing training program depends on the integration of all the learning behaviors in Bloom’s Taxonomy.

The three keys components of this training are:

- Break down the steps of the writing process to meet the specific needs of a social science paper.

- Design an explicit and clear set of instructional scaffolds that build students’ critical thinking about each step of the writing process.

- Set up writing groups and submission procedures for a series of informal and formal assessments.

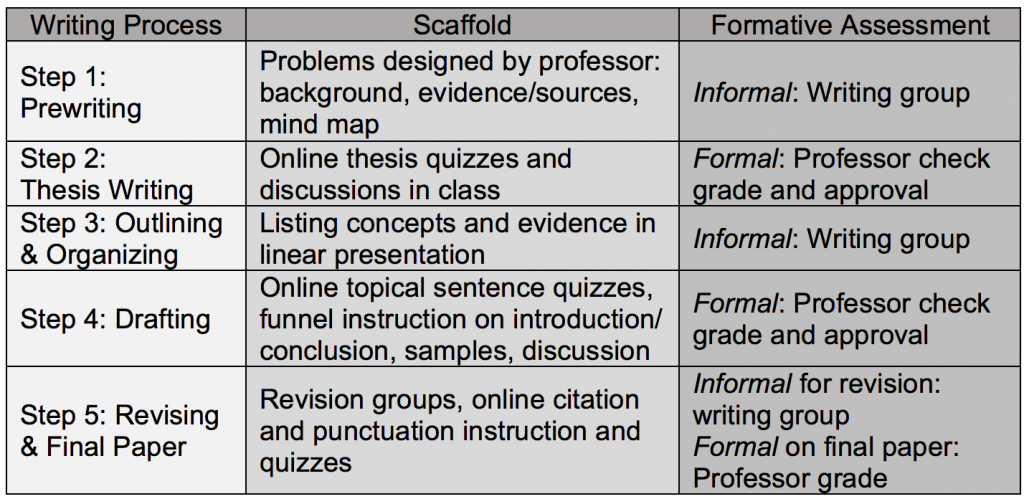

The chart below demonstrates the writing project plan for a GE standard 1500-word history paper.

The real secret sauce in this writing process is the detailed, scaffolded activities in the middle column. Why? Because the professor must be an activator, not a facilitator, of the critical thinking that is involved in the writing process. Some activities and learning behaviors can be completed independently and online, but they should be brought to a professor-led classroom discussion for review and analysis.

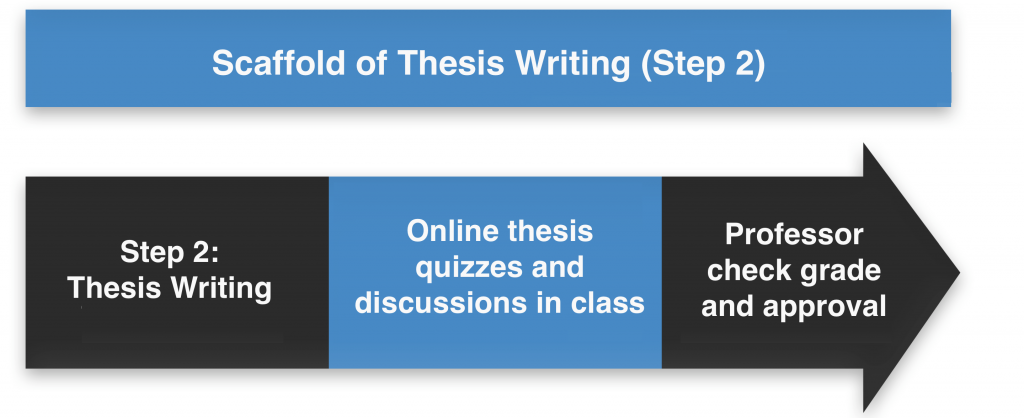

The image below provides a visualization of the breakdown of the thesis-writing step in the essay-writing process. The professor can begin by instructing students as to the qualities of a strong thesis, as well as the markers of a weak thesis. Students then complete an online quiz in which they are asked to select the superior thesis in a choice between two theses. The professor then follows-up by including a discussion and analysis of these quiz items in the next week’s class. A couple of days later, students submit their individual theses to the professor for checking, revising, and approval.

In my estimation, social science professors who want to participate in the generalized improvement of students’ writing level in the lower-division courses will need to contribute 10-15 minutes of classroom time to this project each week. Although this does involve grading the crafted parts of students’ papers twice before grading the end product, it does not take much more time than grading a very bad final paper in which students have been left to their own devices. Detailed, scaffolded activities also require a little bit of time to learn how to activate, but within a couple of semesters, composing them becomes quite simple and will feel like second-nature.

Yes, a professor does have to give up a little bit of time and self-training to teach writing and composition skills effectively. However, in gauging whether or not it is worth your extra time, you only have to remember two numbers: 86% and 88%. These are, respectively, the percentages of college professors and employers who believe that writing effectively is a very important transferable skill-one that is critical to students’ future prospects in the job market.