|

Through my discussions with college instructors, as well as my own experience as a teacher, I have realized that the college classroom discussion with undergraduates can be a somewhat elusive phenomenon. Many aspiring instructors envision going into their first college classroom and engaging in a compelling discourse with students about crucial primary sources in American History, American Government, and World History. The reality soon falls short of the expectation when they have their first disappointing discussion, in which only one or two students participate, and the conversation lasts all of ten minutes. After experiencing this, many instructors soon revert back to the 75-minute lecture. How do we make the elusive classroom discussion into a reality? After much trial and error, I have found some sure-fire ways to prepare and engage my students in the discussion format. Concise, Targeted Readings for Backgrounding Focus with a Primary Source Another aspect of choosing the primary source is either to excerpt it or to divide a longer documentary source into chunks. I will give the chunks subtitles to remind myself of the concepts that I want students to understand clearly. Over the course of the term, I like to select a variety of sources — images, videos or films, music, art, letters, timelines, data, and so on. Once I have a clear idea as to what specific connections between the reading and the source that I want to highlight, the planning becomes much easier. Bring In Another Medium to Pique Interest The Inquiry and the Graphic Organizer I also assign as homework a graphic organizer or close reading questions about the primary source. The students need an incentive to come to class prepared for the discussion. They also need to have it broken down for them into manageable parts so that they can begin to understand what they are analyzing in a field of study that they are not familiar with.

Debriefing Techniques in the Classroom Then, using classroom polling technology, I direct each group to share a concise answer to the historical question at hand. The discussion naturally takes off, because we can compare and contrast what the groups have come up with. It is also helpful to designate a speaker from each group to summarize their group’s discussion. This activity can be done quickly in 15-30 minutes. I have received some of my best student evaluations using this discussion format because my students are able to truly engage with the course materials. These simple tweaks to my classroom discussion strategy have taken on the elusive classroom discussion and have made it a successful reality. For my primary source reader, I use digital essays from Globalyeum. Globalyceum has offered one of their primary source lessons for you to demo in your classroom. Contact [email protected] to gain access to a set of primary source materials. |

Author: Laura Guardino

Using Election 2016 in the Classroom

Here is a problem that many professors have. My syllabus has been set since the start of the semester, and any potential change might throw my students off or change my grading system. But my students are interested in this year’s election, and I do not want to pass up a chance to teach history as it is happening. How can I make it happen online, use no more than 10 minutes of class time each week, and easily incorporate it into my grade point structure?

The many different activities in Globalyceum’s Election 2016: Follow the Vote have provided me with the easy solution to this problem. The first activity I chose was the mock election because I knew my students would appreciate the opportunity to vote and then analyze their votes. For many of my students, this presidential election would be their first as potential voters.

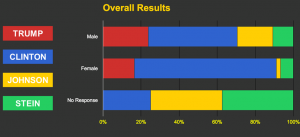

The mock election was online, and it collected not only the vote but demographic data about the voters. I could assign it for homework, and the students could complete it at home in under five minutes. In the following week, I would then be able to throw the results up on the screen for the first five minutes of class time to hold a brief discussion. Globalyceum has organized it so I can manipulate the data with the students, comparing voting patterns of groups–age, gender, ethnicity, education, etc.–and digging a little deeper into the election. Last week, my students completed the first mock poll of opinions about the issues and candidates, and I look forward to a similar and even more interesting discussion with those results this week. If you missed the first round of elections and polls, it is not a problem because there is a second mock election the week of September 26 and a second survey in mid October, followed by the final mock election the week before US voters go to the polls on November 8.

Brief videos (under four minutes) about events of the election is another great feature of Election 2016 that I have chosen to use. The most recent was “The Battleground States.” It not only explained the Electoral College and how it creates the phenomenon of battleground states, but also Dr, Melinda Jackson’s analysis of this year’s battleground. I added my own variation — I showed the video at the start of class and asked the students to rate which candidate had the better battleground state strategy. This in-class assignment took seven minutes, and dramatically enhanced my lecture. I was using the Globalyceum lecture by Jack Rakove, “Three Myths of the US Constitution,” which talks about the Founder’s reasons for creating the Electoral College. This allowed me to make a great connection between past and present. The next video about the debates will be available October 3, and I plan to do a similar strategy of video and then poll.

Globalyceum’s Election 2016 suite of materials also has primary source problems and readings on our electoral system. If you have the time, you can use these in class or as homework. I have chosen to do just the videos and mock elections and polls, but I know other professors who have added one or two of the other activities.

I had the good fortune last fall of talking with Dr. Melinda Jackson, the author of Election 2016. I asked her what was the biggest problem with teaching students American government and history today. She responded quickly–”student political apat hy.” Professors should do more than tell students about politics and government. They also need to turn students into “engaged citizens who can make a difference.” A teacher who brings elections, political processes, and government into the classroom is actually priming students to get involved by voting, volunteering in an election, writing a letter to a representative, or registering others to vote. It only takes 10 minutes a week, but it can make a world of difference.