The reading level of students entering college is rather elusive, but it is usually calculated in one of two ways. One is based upon the national average of placement scores, which indicates that about 50 percent of entering freshmen read at a grade 12 level. Alternatively, “The Nation’s Report Card” of the NAEP indicates that about 38 percent of graduating high school seniors read proficiently at a grade 12 level, which would suggest a proficiency level percentage in the mid 50s for the group that will enter college. In addition to these estimates, a highly publicized study by the Renaissance Learning Organization determined that the reading material of college English classes is on roughly grade 7 level, which led the RLO to conclude that, in reality, college students really don’t read beyond the middle school level.

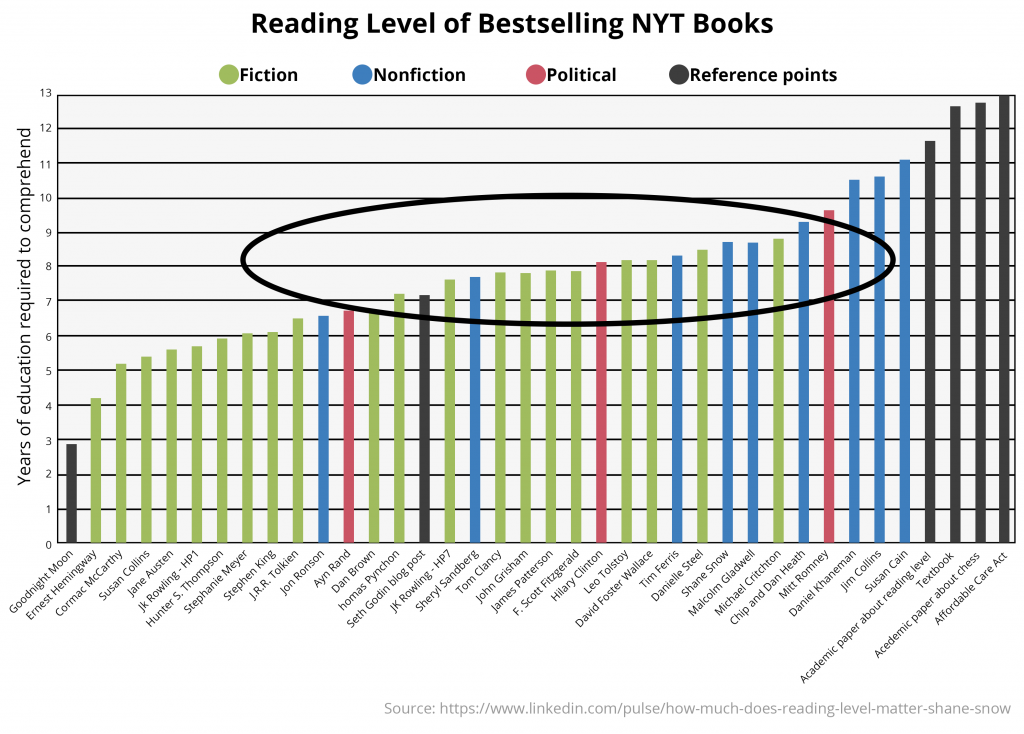

Let’s move beyond the battle of statistics for a moment and look a little more deeply at how the transferable skill of college reading relates to the larger picture of college graduation and employability. The chart below tracks the reading levels of books on the New York Times Bestsellers List, as well as those of other types of literature.

There are a few key pieces of information to note when observing this data. First, the bestselling books fit into a grade 8 reading level (highlighted by the oval). Next, note that fiction literature generally falls within a lower reading level than does nonfiction literature. Finally, notice that academic papers, textbooks, political literature, and government reports–indicated by the bars on the right–are distinctive in that they fall under the much higher difficulty level of grades 11-12.

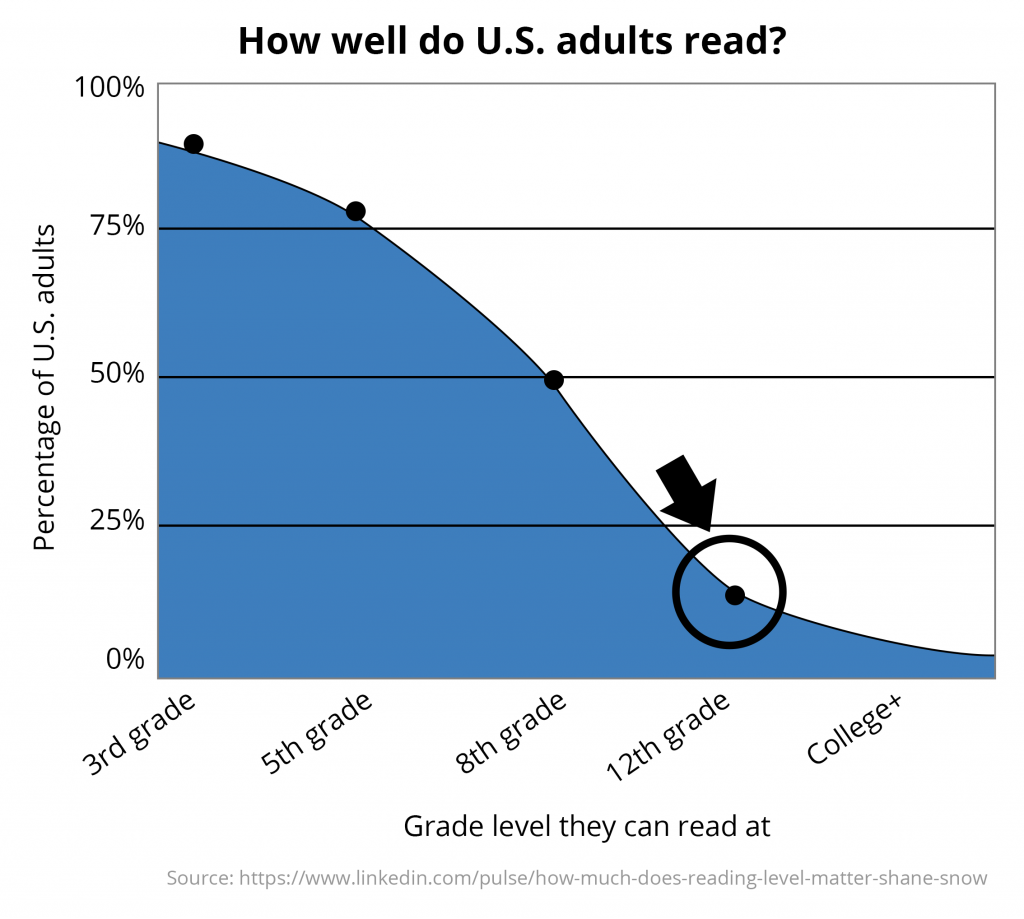

How do we explain this data? First, the median reading level of American adults is around grade 8, as detailed in the chart below. If bestselling authors, such as Malcolm Gladwell, intend to sell books, they need to write for the median audience. Although many people reading Malcolm Gladwell are probably capable of reading at a higher level, a grade level 8 is a comfortable one, for which one doesn’t have to strain, slow down, re-read, and reflect too often.

This observation is very important for college professors because it reveals that there are two types of reading–“ease” reading and “work” reading. What is the difference between grade 8 “ease” reading and the grade 12 “work” reading that is required for academic texts? The three discomforting features of academic texts are:

- Very conceptually-driven or analytically narrative passages (as opposed to simple narrative)

- Difficult, very precise vocabulary

- Complex sentences with lots of dependent clauses contributing a lot of content

While tempting, it would be unwise for professors to eliminate these uncomfortable characteristics, or to “dumb down” their readings. In fact, I want to suggest that academic reading should be thought of as the training ground for “work” reading–that is, the complex memos, reports, data, and topical readings of modern, professional employment. The real takeaway here is that successful, well-educated people prefer to read at grade 8 level, but they work at the level of grade 12 or higher.

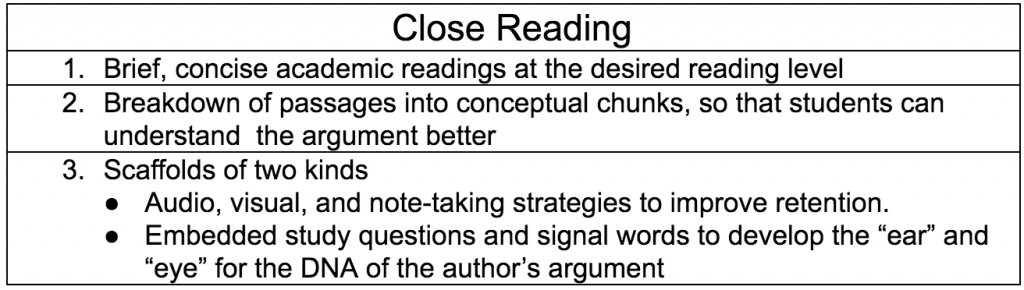

So, what is the strategy for training students to develop a “work” reading mode? Reading specialists tell us that “close reading” is the best way to teach those who read comfortably at grade 8 to cope with and learn how to read less comfortable but necessary grade 11-12 academic texts. The chart below lists the three basics of this strategy.

In the next blog, I will describe the mechanics of close reading in the lower division classroom.