College professors spend a great deal of classroom time lecturing about the complex knowledge of their disciplines for the following two reasons:

- Tradition

- The assumption that college-bound students already have the skills necessary to utilize this sophisticated knowledge.

While the traditional lecture setting should certainly not be underestimated (an issue which I will discuss later on), the assumption that students have the skills to work with the complex knowledge that is dealt with in lectures is wrong. Colleagues say that they understand this, but I think the achievement gaps of high school graduates who enter college are even greater than they realize.

Transferable skills allow a person to process and manipulate any body of information, whether general or disciplinary. For the sake of this discussion, we will start by grouping key transferable skills into three broad categories – reading, analytical reasoning, and writing. Studies of entry-level college freshmen show that about half read at grade 12 level, just 37 percent have the very basic analytical skills necessary to work with information, and only 27 percent write at a grade 12 level.

The data visualized in the chart above has important implications concerning college graduation rates. The 27 percent of college-bound students who are “proficient” (i.e., at a grade 12 level) in all three areas of proficiency probably have a very high rate of graduation. At the other end of the spectrum, about 40 percent are “not proficient” in all three areas, with skills typically below mid-grade 9 level. This problematic deficit is very difficult to make up in college. In fact, over half of those that belong in this 40 percent are probably also a large portion of the 22 percent of students nationwide who drop out of college in their first year. They simply can’t keep up.

This leaves a remaining 33 percent of the students, a group that I will call “near-proficient,” or ranging from grade 9 to grade 12 in the three skill areas. The good news is that most of the proficient and near-proficient students end up graduating. A good percentage of the latter, however, struggle and take 6 years and more to graduate. Moreover, they are not usually among the most stellar graduates. I argue that an emphasis on transferable skills in the first two years of college would help all near proficient and some 5 percent or so of the not proficient students to catch up academically, ensuring graduation. If they did graduate, it would increase the national graduation rate to 65 percent, a very desirable goal for American social mobility.

Transferable Skills → College Graduation + Employability

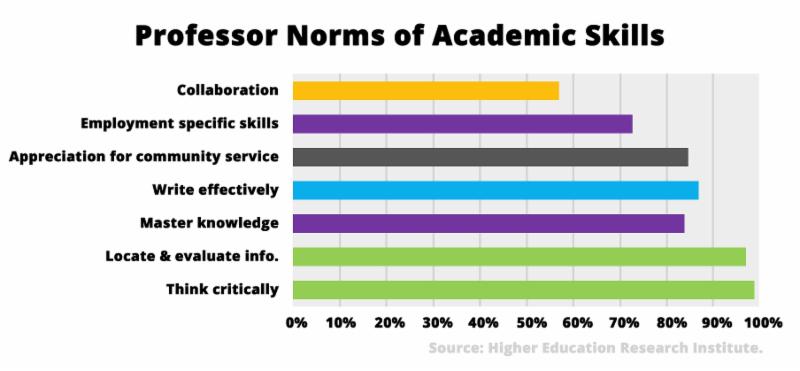

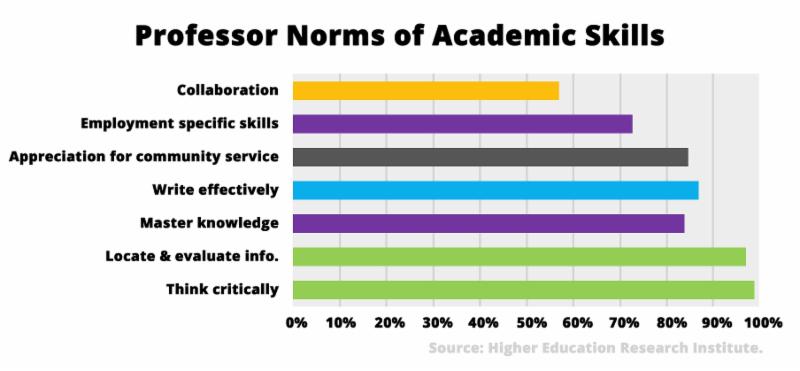

The following two surveys demonstrate a further consideration that involves a more focused concentration on teaching and expecting transferable skills to be developed in students within the first two years of college. This will lead to college graduation for an additional seven to ten percent of students and will also improve employability. This first survey is of college professors who identified the expectations of students who seek a bachelor’s degree. Note that, while the specific transferable skill of “mastery of knowledge” is given very high ratings, the other specific skills of critical thinking and writing effectively are also highly valued.

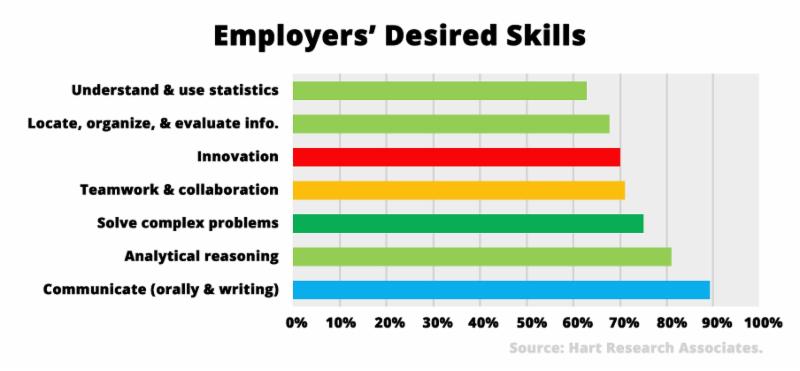

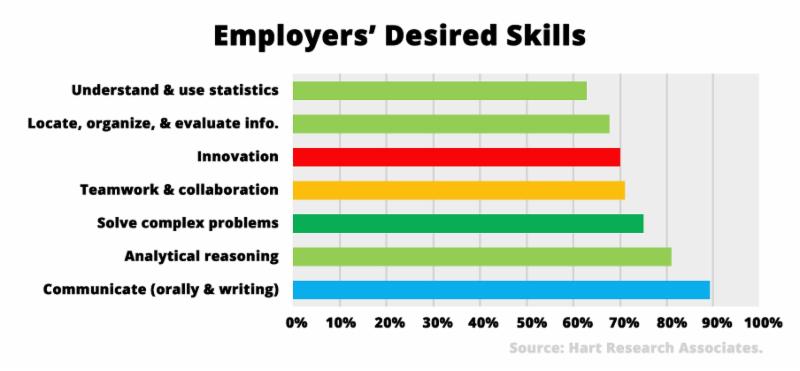

Even more revealing is the survey of employers who reveal what they are looking for in the people that they hire. Note, here, that mastery of knowledge (and even job skills) does not even make the list. Employers emphasize transferable skills almost exclusively, especially “communicating, orally and in writing,” “analytical reasoning,” and “solving complex problems” — all three of which are at the top of their lists. Both groups also rate research, collaboration, and the evaluation and use of information very highly.

If these specific transferable skills were to be applied in a college classroom setting, a visualization of the result would look something like the graphic below. The triangle shape you see is known as Bloom’s Taxonomy, used here to categorize and weigh the amount of time a student spends demonstrating learning behaviors. In many lower-division college classes, the lion’s share of the curriculum and the time is devoted to mastery of knowledge (which is at the bottom of the pyramid), while critical thinking and writing and research–the transferable skills that are prized by the employers in our surveys–garner less attention in the education setting.

However, the classroom that concentrates on transferable skills through the disciplinary content would turn Bloom’s Taxonomy from a pyramid to a ziggurat. “Mastering knowledge” would still carry a good deal of weight, not only due to the professor’s

lectures, but also through the amount of assigned reading and studying

of information and texts that is required of students to do on their own. After all, the learning behaviors of Remembering and Understanding are foundational. But Analyzing and Applying problems, evidence, and sources characteristic of the discipline would be added, as would Creating and Evaluating in the forms of writing, research, and presentation, using disciplinary knowledge, problems, and evidence.

As you can see, the weight of classroom time is shifted up the scale from an almost singular interest in mastery of knowledge with read/study and listen skills to analyze and eventually write/research. Note the professor is shifting the weight of time and attention, not turning the classroom upside down.

This blog is part two of a six-part series. In future blogs, I will continue to explore how we can collectively improve graduation rates and, as a result, provide ladders of opportunity to our youth. Part one of the series is available here: College Professors and American Dreams.