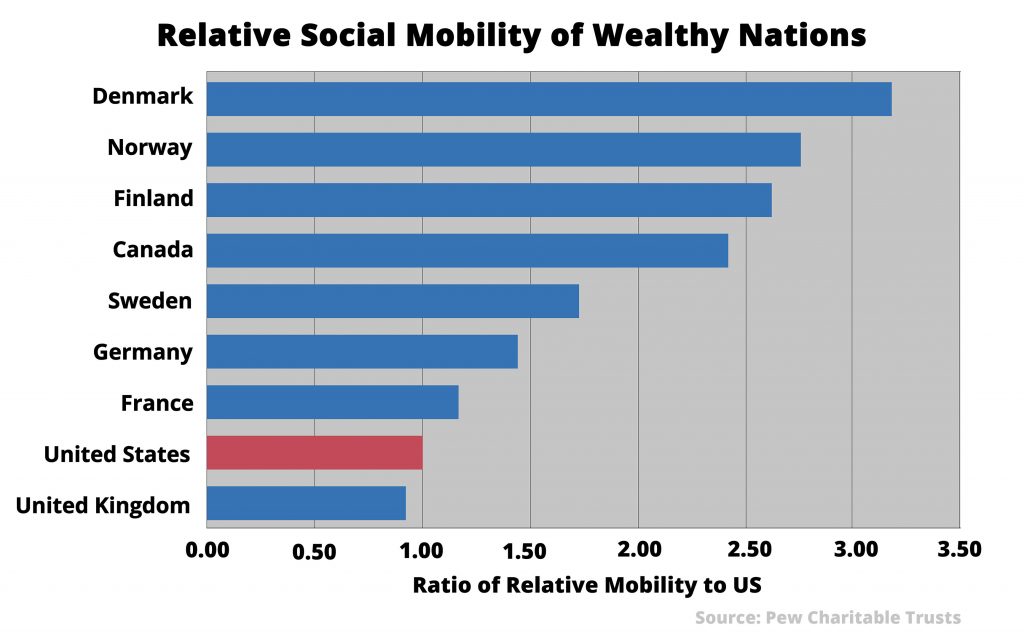

I emphasize social mobility because it is an important underlying theme in today’s political climate on both sides of the aisle. It is obvious that Americans treasure this “Dream” and have become very disappointed that it does not seem to be coming true for them. They are frustrated by what they perceive as their leaders’ lack of sufficient attention to this massive problem, and they want a fix sooner rather than later.

As you might expect, the root cause of this decreasing relative social mobility is complex, and there are no easy ways to repair massive socioeconomic shifts like this one. Globalization and, even more importantly, automation have resulted in the loss of many US jobs–especially lower-skilled fields such as manufacturing. These trends, regardless of political efforts, will continue to accelerate. To revive the American Dream, middle and working class Americans need leaders and institutions that help them work with and around these long-term economic trends.

This brings me to a very important finding uncovered in these studies. In America, a parent’s income level–and, by extension their education level–is a far more predictive factor of a child’s socioeconomic future than it is in any other developed country. Achieving the American dream has almost become dependent upon completing a college education.

College Graduation → Employment → Social Mobility

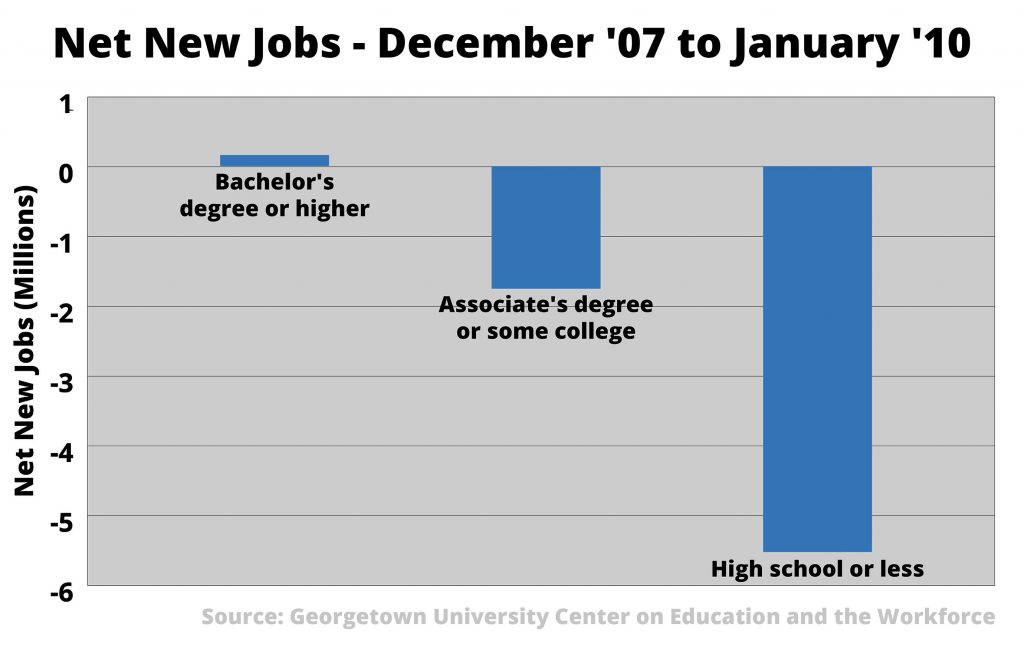

The graph below illustrates this finding. The net new jobs figure is an important statistic for economists because it anticipates future employment trends. In a recession, businesses go through the painful processes of laying off employees and shutting down facilities in order to then take advantage of their newly cleaned slate to reposition their companies for the future. This means hiring employees who they believe will help the company thrive in the long run. Thanks to the following study, we now know who these new employees are.

From 2007-2009, this happened:

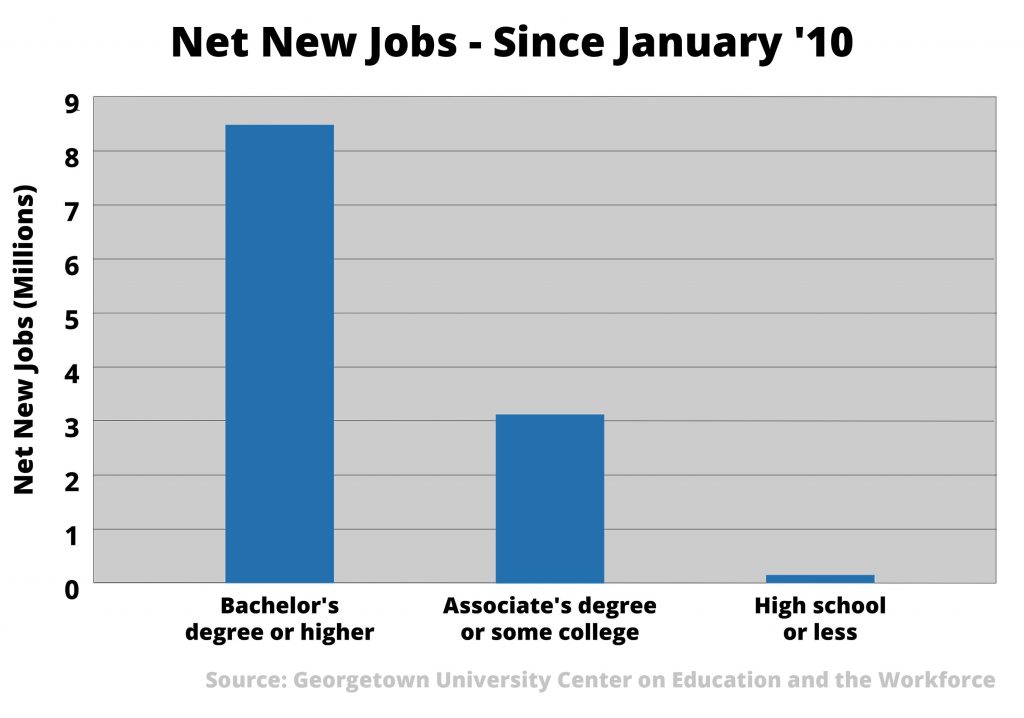

. . . and since 2010, this development followed:

Over 70% of new jobs since January 2010 went to people with a bachelor’s degree or higher, while less than 1% of the new jobs went to people without a college degree. The Great Recession practically took down the “Applicants Wanted” sign for high school graduates, while also maintaining a climate that was not particularly welcoming to graduates with just some college.

According to the National Student Clearinghouse, the 6-year college graduation rate in the US currently hovers in the low 50s percent range and, unfortunately, has ticked down slightly in the last few years. The takeaway for college professors is this: concentrate on what will move a significant number of the “some college” students into the graduated column. What is a significant number? Just a 10 percent increase in the national college graduation rate would elevate the US to near the top of the world list in relative social mobility.

As discussed, there is a significant correlation among the college graduation rate, employability, and social mobility. While the 50/50 graduate-to-dropout rate in the American higher education system has been around for a while, changing it to 60-40 is within the power of professors and educators. In fact, the most important question facing professors today is, “am I willing to take on this challenge?”